السلام عليكم و رحمة الله و بركاته

Implied status

Last time we went into I’rab and how words commonly show their status using vowels. This kind of change is called لَفْظِي (“pronounced”) because its’s explicit and is heard clearly. Today, we’re going to “look beyond the obvious” and cover something called “implied status”. There are some words whose endings do not change even when they move between states due to one of three obstacles preventing that change (explanation to follow):

- Impossibility of pronouncing it

- Difficulty/heaviness in pronouncing it

- Association with something that brings another vowel on it

Let’s look at a sentence that has examples of all three in it:

يَدْعُو الفَتَى وَ القاضِيْ وَ غُلامِيْ (“The youth, the judge and my servant boy call”)

- The word الفَتَى (“the youth”) ends with an alif (which is impossible to put a vowel on)

- When we used the the word يُسافِرُ (“he travels”), it had a dhammah at the end in its original state of رفع. Likewise, the word يَدْعُوْ (“he calls”) was originally يَدْعُوُ (with a dhammah at the end). In this case, it is possible to put a vowel on the last letter (و), but it’s just harder to pronounce that way, so it’s يَدْعُوْ (with a sukun at the end) instead.

- القاضِيْ was originally القاضِيُ (with a dhammah), but to make the pronunciation easier, the dhammah was dropped.

- The word غُلامِيْ (“my servant boy”) is really two words attached together: غُلام (“servant boy”) and the ي that means “me”. It’s not impossible or difficult to pronounce the vowels on the letter م here. What happened here instead is that the ي of the “me” comes with a kasrah on the letter before it(م), so there’s no room to put a dhammah on it.

Taking a closer look a the sentence, we see why the words don’t have dhammah at the end like they should normally do:

| Word in the sentence | State and reason | Intended vowel and reason for implied status |

| يَدعُو | رَفْع – There is nothing else that forces it to another state | Dhammah – Heaviness of pronunciation |

| الفَتى | رفع – Doer of the action يَدْعُوْ | Dhammah – Impossibility of placing the dhammah at the end |

| القاضِيْ | رفع – Joined by و to الفتى | Dhammah – Heaviness of pronunciation |

| غُلام | رفع – Joined by و to الفتى | Dhammah – The place for dhammah already has kasrah due to the ي that associates word to the speaker |

As for لَنْ يَرْضى الفَتَى وَ القاضِيْ وَ غُلامِيْ (“The youth, the judge and my servant boy will not be pleased”) :

| Word in the sentence | State and reason | Intended vowel and Reason for implied status |

| يَرْضى | نَصب – The لن causes نصب on the present tense verbs | Fathah – Impossibility of placing fathah at the end |

| الفَتى | رفع – Doer of the action يَرْضى | Dhammah – Impossibility of placing the dhammah |

| القاضِيْ | رفع – Joined by و to الفتى | Dhammah – Heaviness of pronunciation |

| غُلام | رفع – Joined by و to الفتى | Dhammah – The place for dhammah already has kasrah due to the ي that associates word to the speaker |

As for إِنَّ الفَتى وَ غُلامِي و القاضِيَ لفائِزُونِ (“Indeed the youth, my servant boy and the judge are winners”):

| Word in the sentence | State and reason | Intended vowel and reason for implied status |

| الفَتى | نَصب – The إنَّ puts an اسم into نَصب | Fathah – Impossibility of placing the fathah at the end |

| غُلام | نصب – Joined by و to الفتى | Fathah – The place for fathah already has kasrah due to the ي that associates word to the speaker/td> |

| القاضِيَ | نصب – Joined by و to الفتى | Fathah – The status is NOT implied and the fathah IS pronounced in the case of نَصب |

And finally, مَرَرْتُ بِالْفَتى وَ غُلامِي وَ الْقاضِي (“I passed by the youth, my servant boy and the judge”):

| Word in the sentence | State and reason | Intended vowel and reason for implied status |

| الفَتى | جَرّ – The letter ب that precedes it is one of the particles of خفض | kasrah – Impossibility of placing the kasrah at the end |

| غُلام | جَرّ – Joined by و to الفتى | kasrah – The place for kasrah already has kasrah due to the ي that associates word to the speaker |

| القاضِيْ | جَرّ – Joined by و to الفتى | kasrah – Heaviness of pronunciation |

From what we’ve seen just now:

- Words that inherently end with ا, have all the vowels are implied upon them due to the impossibility of placing vowels on the ا. These words are called مَقْصُور (shortened). Sometimes you will see this alif written as ى (like a ي without the two dots). Some examples:

- الفَتى (youth)

- عَصا (stick)

- حِجى (intelligence)

- رَحى (hand mill)

- رِضى (pleasure)

- Words that inherently end with ي have only the dhammah and kasrah implied on them due to the heaviness of pronouncing the dhammah. As seen above, because a fathah is lighter in pronunciation then a dhammah and is not difficult to pronounce, we will see/hear the fathah when the word is in نصب status. These words are called مَنقُوص (deficient) because they end with ي, which is one of the “defective” letters. Some examples:

- القاضِي (the judge)

- الداعِي (the caller)

- الغازِي (the raider)

- الساعي (the messenger)

- الآتِي (the one who comes)

- الرامِي (the thrower)

- Like مَقْصُور words, words that are attached to the ي of the first person (i.e. “me”) have all the vowels are implied upon them. In each of the examples below, the letter before the ي already has a kasrah on it, so it can’t accept any other vowel on it.

- غُلامِي (my servant boy)

- كِتابِي (my book)

- صَدِيقِي (my friend)

- أبِي (my father)

- أستاذِي (my teacher)

- “Inherently” means that it is part of the original root structure of the word, and not something added to it later.

البِناء (“Fixed” endings on words)

We’ve seen how words change status and also how words can implicitly change status, even if the ending is prevented from changing. These words are called مُعْرَب (words that take grammatical status).

In opposition to that are words that do not change status at all, whether explicitly or implicitly. They are called مَبْنِي words. The concept of بِناء comes with the meaning of putting something on top of something else with the intention of stabilizing the structure and making it last, which makes sense because مبني words firmly stick to their ending. In grammar, a مَبني word is a word:

- Whose ending sticks to one condition, and

- The reason for that stickiness is not due to a grammatical influence or defective letter (i.e. not one of the three obstacles at the beginning of this segment).

In other words, it sticks to a certain ending for its own sake, not because of anything else. Some examples:

- كَمْ (“How much?”) and مَنْ (“Who?”) stick to the silent vowel, sukoon in their ending

- هاؤلاءِ (“these”), حَذامِ (a woman’s name), and أمسِ (“yesterday”) stick to kasrah

- مُنْذُ (“since”) and حَيْثُ (“where”) stick to dhammah

- أيْنَ (“Where?”) and كَيْفَ (“How?”) stick to fathah

From this, we see that a مبني word can be fixed one of four endings: sukoon, kasrah, dhammah or fathah.

After the explanation of each of these, knowing the definitions of مُعْرَب and مَبْنِي is not difficult:

مُعْرَب: Whatever’s ending state changes, explicitly or implicitly, due to external influences

مَبْنِيّ: Whatever’s ending stays on one state, due to other than an external influence or having defective letters.

From the Quran

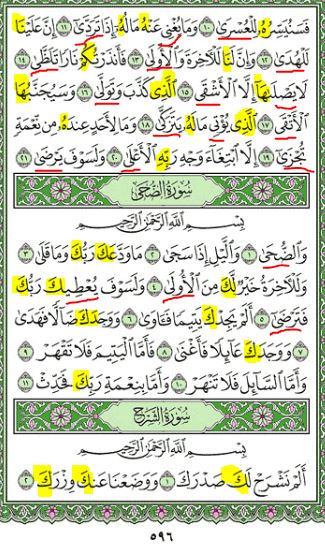

Let’s look at some examples of fixed words (highlighted) and words with implied status (underlined in red) from a page of the Quran. My annotation of 92:9 through 94:3 looks like:

Some comments:

- العُسرى is in خفض because of the لِ before it, but because it ends in ى, we won’t see a kasrah. It is مَقصُور because it ends with ألِف مَقصُورَة (an ا that looks like a ي)

- عَلَينا is really على + نا, but attached pronouns like (نا {us/our} and كَ {you, your}) are fixed. نا is fixed on sukoon so we won’t be seeing a kasrah on it, even though the على before it is one of the particles of خفض. The vast majority of pronouns are مبني words.

- Like the word القاضي, the verb يُعْطِيْ is مَنْقُوص. Can you find an indicator that tells us it’s a verb?

- Like the word الفَتى, the verb تَرْضى is مَقْصُور. Can you find an indicator that tells us it’s a verb?

Questions

- What is بِناء?

- What is a مُعْرَب word?

- What is a مَبْنِي word?

- How many types of change are there?

- What is meant by change that is لَفْظِي (pronunciation-wise)?

- What is meant by change that is تَقْدِيرِي (implied)?

- What are the three reasons for implied changes?

Until next time, السلام عليكم و رحمة الله و بركاته

Like this post? Simply enter your e-mail and click “Yes, include me!” for updates

As Salaamu ‘Alaikum

Thank you so much for this work. I am an American Muslim learning Arabic. I work with a group of people and we are pretty much self-teaching ourselves. Your lessons are far above many I have used. You explain very well, and your focus is Qur’anic Arabic, while also infusing some Modern Standard Arabic. I like that. We are only up to lesson 6 in our group studies, but I am moving ahead, (because I have more time). I pray Allah continues to bless you in this and your future endeavors.

Wa alaykum as salaam,

Jazakillahu khayran for your kind words and ameen to your duas. We thank Allah that you and others are continuing to benefit from these lessons. I don’t know which book/lesson plan your group is following, but this grammar series runs off the ordering found in al-Ajurroomiyyah. The whole series is on the resources page, but if you sign up with your email you can get one post straight to your inbox every few days and avoid having to remember to come back to the site to read each chapter.

– Mustafa

Don’t you mean fatha here?

عَلَينا is really على + نا, but attached pronouns like (نا {us/our} and كَ {you, your}) are fixed. نا is fixed on sukoon so we won’t be seeing a kasrah on it, even though the على before it is one of the particles of خفض. The vast majority of pronouns are مبني words.

As-salaamu alaykum,

No I really do mean a sukoon here 🙂 When we say something is “fixed” (مبنيّ), it will be fixed on whatever is on the last letter. Keeping that in mind and seeing that the ا in نا is silent, we say that it’s fixed on sukoon.

Wallahu a’lam

please what is the differences between mani and binaa