السلام عليكم ورحمة الله وبركاته,

We’re still talking about grammatical followers of a word that come after it and follow it in status. We’ve done النَّعْت (The adjective). Now we’re going to look at the عَطْف (conjunction), starting with some particles that are used to join between words in a sentence:

ِحُرُوْف العَطْف (The particles of conjunction)

ِوَحُرُوْفُ العَطْفِ عَشْرَةٌ، وَهِيَ: الْوَاوُ، وَالْفاءُ، وَثُمَّ، وَأَوْ، وَأَمْ، وَإمّا، وَبَلْ، وَلا، وَلَكِنْ، وَحَتَّى فِيْ بَعْضِ المَواضِعِ

And the particles of conjunctions are 10. They are the letters و (waw) and ف (fa), ثُمَّ (thumma), أَوْ (aw), أَمْ (am), إمّا (immaa), بَلْ (bal), لا (laa), لَكِنْ (laakin), and حَتّى (hattaa) – in some situations

The word عَطْف (‘atf ) in the normal sense means “to incline to something”. If you say عَطَفَ فُلانٌ عَلى فُلانٍ (“Somebody had ‘atf for somebody”), it means that he inclined toward him and had affection for him.

In grammar, they’re two kinds of ‘atf :

- عَطْف البَيانِ (‘atf al-bayaan) – This is an explanatory addition that either clarifies the meaning (if after a definite noun) or restricts the meaning (if after an indefinite noun). It has to match what it’s following in status

- جاءَ مُحَمَّدٌ أَبُوْكَ (“Muhammad, your father, came”) – محمدٌ is a definite noun (it’s a proper name) in the state of raf’ because it’s the doer of جاء (“came”). To make it clear exactly who you mean by “Muhammad”, you follow up with أبوُكَ (“your father”). Your addition also has to be in raf’ so you useو (like how we show raf’ for the Five Nouns )

- مِنْ ماءٍ صَدِيْدٍ (“from water, festering water“) – ماءٍ (“water”) is an indefinite noun in jarr because of the particle مِنْ before it. To restrict the meaning of this water, the word صََدِيدٌ (“pus”) comes after it.

- عَطْف النَسْقِ (‘atf al-nasq) – This is a grammatical follower that is connected to what it’s following by putting one of the حروف العطف (connective particles) in between, and there are 10 of these particles:

- و (“and”) – Gives the most general way to join between things. In جاءَ مُحَمَّدٌ وَعَلِيٌّ (“Muhammad and Ali came”), the و is used to combine two things that with each other. If one comes before the other, و can be used, but it does not imply ordering. جاءَ زَيْدٌ وَ خالِدٌ could mean that Zaid came first or that Khalid came first. You can assume that they both came, but not who came first.

- When mentioning two things, and one is more important or concerning, it’s appropriate to start with that, as in جاءَ السَيَّدُ وَعَبْدُهُ (“The master and his slave came”)

- فَ (“immediately after”) – Used to give ordering and immediate follow up. قَدِمَ الْفُرْسانُ فَالْمُشاةُ would mean “The calvary arrived, then the foot soldiers”, with no gap in between

- ثُمَّ (“a while after”) – Used to give ordering with a delay in follow up. When talking about when prophets were sent we could say أَرْسَلَ اللهُ مُوْسَى ثُمَّ عِيْسَى ثُمَّ مُحَمَّدًا عَلَيْهِمُ السَّلامُ (“Allah sent Moses, then Jesus, then Muhammad, peace be upon them”) using ثُمَّ between them because of the interval between their prophethoods

- أَوْ (“or”) – Can be used for several meanings, including:

- تَخْيِيْر (Giving a choice between options without allowing them together). An example would be تَزَوَّجُ هَنْدًا أَوْ أُخْتَها (“Marry Hind or her sister”). One can marry Hind or her sister, but not both

- إباحَة (Giving feasible options, along with allowing them together). For example, ادْرُسِ الْفِقْهَ أَوِ النَحْوَ (“Study fiqh [Islamic law] or grammar”), but there’s nothing wrong with taking both together

- شَكّ (doubt) – If you’re not sure which of two people arrived, you’d say قَدِمَ زَيْدٌ أَوْ عَمْروٌ (“Zayd or ‘Amr arrived”)

- تَحْيِيْر (causing confusion) – You know the answer to someone’s question, but you use “or” to confuse them. If someone asks مَنِ الذِيْ قَدِمَ؟ (“Who is the one who arrived?”) and you know the answer but want to confuse him, you’d reply with زَيْدٌ أو عَمْروٌ (“Zaid or ‘Amr”)

- أَمْ (“or”) – Used to seek a specific answer after using أ for a question

- Simply using أ makes a yes/no question. If you ask أدَرَسْتَ الْفِقْهَ (“Did you study fiqh?”), they would simply give a yes or no.

- Using أم makes it a multiple choice question. أدَرَسْتَ الْفِقْهَ أَمِ النَّحْوَ (“Did you study fiqh or grammar”) is not a yes/no question. It’s expecting an answer like دَرَسْتُ الفِقْهَ (“I studied fiqh”) or دَرَسْتُ النَحْوَ (“I studied grammar”)

- It can also work like بَلْ (“rather”), in some situations. I’m not going into that level of detail here because we’re focusing on the grammatical effect these particles have, but here’s an example for you:

- In the ayah أَمْ تَأْمُرُهُمْ أَحْلَامُهُم بِهَٰذَا ۚ أَمْ هُمْ قَوْمٌ طَاغُونَ (“Or do their minds command them to [say] this, or are they a transgressing people?” ) [52:32], we could treat the second أم like it’s بلْ and translate accordingly: “… rather they are a transgressing people”)

- إِمّا (“either/or”) – it’s similar to أو (“or”)

- فَشُدُّوا الْوَثَاقَ فَإِمَّا مَنًّا بَعْدُ وَإِمَّا فِدَاءً (“then secure their bonds, and either [confer] favor afterwards or ransom [them]” – 47:4)

- تَزَوَّجْ إِمّا هِنْدًا وَإمّا أُخْتَها (“Marry either Hind or her sister”)

- There is a debate about this one. In short, it’s probably not one of the actual particles of conjunction, but I’m including it here because the author of الآجُرومِيَّة considered it so and for the sake of completeness.

- بَلْ (“rather/instead”) – Used for إضراب (turning away) from what you’ve said and applying it to something else. Two conditions for بَلْ are (1) only a single word (no sentences or semi-sentences) can come after it and (2) you cannot use it after a question. For example:

- In ما جاءَ مُحَمَّدٌ بَلْ بَكْرٌ, you say ما جاءَ مُحَمَّدٌ (“Muhammad didn’t come”) and then follow up with بَلْ بَكْرٌ (“rather, Bakr [didn’t come]”)

- You say قَدِمَ زَيْدٌ (“Zayd arrived”), then follow up with بَلْ عَمْروٌ (“rather, ‘Amr [arrived]”)

- In both of these, you cancel what you said about the first person and then apply it to the second one

- لا (“not”) – a conjunctive particle that negates for what’s after it the same thing you declared for what’s before it.

- In جاءَ بَكْرٌ لا خالِدٌ (“Bakr came, not Khalid”), you say جاءَ بَكْرٌ (“Bakr came”) and then you negate that Khalid came simply by adding لا خالِدٌ

- لكِنْ (“but”) – pronounced “laakin”. You confirm what’s said before it and confirm the opposite for what’s after it. It has to come after a negation (“no/not”) or a prohibition (“Don’t…!”), and only a single word must be after لكن, not a sentence or semi-sentence

- In لا أُحِبُّ الْكُسالى لكِنْ الْمُجْتَهِدِيْنَ (“I don’t love lazy people, but [I do love] hard workers”) – You confirm that “I don’t love lazy people” by saying لا أُحِبُّ الكُسالى. Then you confirm the opposite (“I do love…”) for hard workers by adding لكِنْ الْمُجْتَهِدِيْنَ (“but [I do love] hard workers”). الكُسالى is in nasb because it’s the object of أُحِبُّ, so its follower المُجْتَهِدِيْنَ also has to be in nasb (with a ي instead of و).

- لكن came after negation لا, and there is only one word after it (المُجْتَهِدِيْنَ)

- In لا أُحِبُّ الْكُسالى لكِنْ الْمُجْتَهِدِيْنَ (“I don’t love lazy people, but [I do love] hard workers”) – You confirm that “I don’t love lazy people” by saying لا أُحِبُّ الكُسالى. Then you confirm the opposite (“I do love…”) for hard workers by adding لكِنْ الْمُجْتَهِدِيْنَ (“but [I do love] hard workers”). الكُسالى is in nasb because it’s the object of أُحِبُّ, so its follower المُجْتَهِدِيْنَ also has to be in nasb (with a ي instead of و).

- حَتّى (“up to including/even”), in some places

- it’s used for gradualization (what you said is applied, a little at a time) and giving an endpoint

- يَمُوْتُ النّاسُ حَتَّى الْأنْبِياءُ (“People will die, even the prophets”)

- If what’s after حَتّى is a sentence we say that حَتّى is for starting purposes (ابْتّدائية) and is not for عطف. It’s used to start a sentence and the mubtada’ will come after it and be in raf’.

- جاءَ أًصْحَابُنا حَتَّى خَالِدٌ حاضِرٌ (“Our companions came, even Khalid is present”)

- حَتّى is one of the particles of jarr, so sometimes it will put the word after it in jarr as in حَتَّى مَطْلَعِ الْفَجْرِ (“Until the emergence of dawn”)

- So, in some contexts حتى comes for ‘atf (and the word after حتى will be a grammatical follower of what’s before it), in others it will come to put the word after it in jarr and yet others إبْتِداء (particle of inception, and the word after it is in raf’ as the beginning of a sentence). That’s why we say “some situations” when we mention حَتّى.

- This example illustrates the three types of حتى (hattaa): أكلتُ السمكةَ حتى رأسها (“I ate the fish up to or up to including its head”)

- If we read رأسِها with kasrah on the س, then حتى is a particle of jarr, and it would mean the fish was eaten up to, but not including the head. The meaning would be “I ate the fish, up to the head”

- If we read رأسَها with fathah, حَتَّى is a conjunctive particle and because السَمكَةَ is in nasb as the object of eating, رأسَ will also have nasb, with a fathah on it, and the meaning is that the fish was eaten, including the head. The meaning would be: “I ate the fish, even the head”

- If we read رَأسُها with a dhammah and with raf’ it is حَرْف إبْتِداء (particle of inception), it would be the start of a separate sentence. رَأسُه is the mubtada’ of the new sentence and its omitted khabar is assumed as: مأكولٌ (“eaten”, i.e. even the fish’s head was eaten). The meaning of it all would be be two sentences: “I ate the fish. Even the head [was eaten]”

- it’s used for gradualization (what you said is applied, a little at a time) and giving an endpoint

- و (“and”) – Gives the most general way to join between things. In جاءَ مُحَمَّدٌ وَعَلِيٌّ (“Muhammad and Ali came”), the و is used to combine two things that with each other. If one comes before the other, و can be used, but it does not imply ordering. جاءَ زَيْدٌ وَ خالِدٌ could mean that Zaid came first or that Khalid came first. You can assume that they both came, but not who came first.

The rule for conjunctions

فَإنْ عَطَفْتَ بِها عَلَى مَرْفُوْعٍ رَفَعْتَ، أَوْ عَلَى مَنْصُوْبٍ نَصَبْتَ، أَوْ عَلَى مَخْفُوْضٍ خَفَضْتَ، أَوْ عَلَى مَجْزُوْمٍ جَزَمْتَ، تَقُوْلُ: “قامَ زَيْدٌ وَعَمْروٌ، وَرَأيْتَ زَيْداً وَعَمْراً، وَمَرَرْتُ بِزَيْدٍ وَعَمْروٍ، وَزَيْدٌ لَمْ يَقُمْ وَلَمْ يَقْعُدْ”

If you use them for joining to a raf’-ized word, then you raf’-ize, or a nasb-ized word, then you nasb-ize, or a khafdh-ized word, then you khafdh-ize, or a jazm-ized word, then you jazm-ize. You say قامَ زَيْدٌ وَعَمْروٌ (“Zayd and ‘Amr stood”), رَأيْتَ زَيْداً وَعَمْراً (“I saw Zaid and ‘Amr”), مَرَرْتُ بِزَيْدٍ وَعَمْروٍ (“I passed by Zaid and ‘Amr”) and زَيْدٌ لَمْ يَقُمْ وَلَمْ يَقْعُدْ (“Zaid did not stand and did not sit”)

These 10 particles make whatever is after them have the same state as what’s before them. You can tell from the examples above how that works, along with a few more below:

- قابَلَنِيْ مُحَمَّدٌ وَخالِدٌ (“Muhammad and Khalid met me”) – مُحَمَّدٌ is the doer of قابلَ (“met”) and خالِدٌ is joined to it with و. Both are in raf’ with a dhammah to show it

- قابلَتُ مُحَمَّدًا وَخالِدًا (“I met Muhammad and Khalid”) – مُحَمَّدًا is the object of قابلْتُ (“I met”) and خالِدًا is joined to it with و. Both are in nasb with a fathah to show it

- مَرَرْتُ بِمُحَمَّدٍ وَخالِدٍ (“I passed by Muhammad and Khalid”) – مُحَمَّدٌ is jarr-ized by the particle بِ, and خالِدٍ is joined to it with و. Both are in jarr with a kasrah to show it

- لَمْ يَحْضُرْ خالِدٌ أوْ يُرْسِلْ رَسُولًا (“Khalid not attend or send a messenger”) – يَحْضُرْ is in jazm because of لَمْ and يُرْسِلْ is joined to with with أو. Both are in jazm with a sukun to show for it

Tip: From these you can see that nouns are joined to nouns and verbs are joined to verbs.

From the Quran

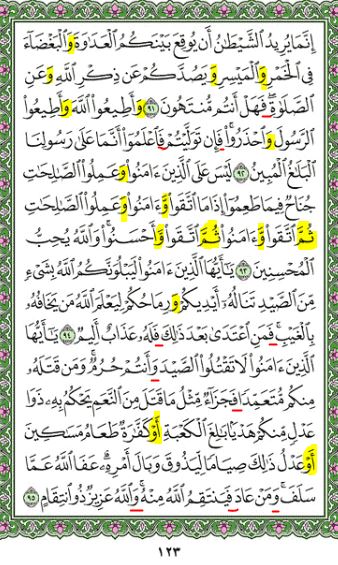

Highlighted below are حروف العطف (conjunctive particles) from 5:91-95.

- The most common connector is وَ

- Notice how what’s being connected and what it’s connected always have the same state

- The verb يَصُدَّ in يَصُدَّكُمْ is connected to يُوْقِعَ, which is in nasb because of أَنْ (verbs connect to verbs and nouns connect to nouns)

- Words underlined are red look like conjunctive particles, but are serving a different purpose (i.e. not being used to connect words that have the same status).

- ف and و can sometimes be use for اسْتِئناف (beginning a sentence), as in َفَهَلْ أنْتُمْ مُنْتَهُوْن (“[So] will you not desist”?) and َوَمَنْ عاد (“[but] whoever returns…” )

- ف can be used to as a reply to a condition (“then”), as in فَلَهُ (“then for him”) and فَيَنْتَقِمُ اللهُ مِنْهُ (“[then] Allah will take retribution from him”)

- و can be used to describe a condition (“while”), as in وَأنْتُمْ حُرُمٌ (“[while] you are in the state of consecration for pilgrimage”)

Exercises

See if you can break down these sentences (what each word is, its status if it has one and its ending)

- ما رَأيْتُ مُحَمَّدًا لَكِنْ وَكِيْلَهُ (“I did not see Muhammad, rather his agent”)

- زارَنا أُخُوْكَ وَصَدِيْقُهُ (“Your brother and his friend visited us”)

- أخِيْ يَأكُلُ وَيَشْرَبُ كَثِيرًا (“My brother eats and drinks a lot”)

Questions

- What is an عَطْف?

- How many kinds of عَطْف are there?

- What is an عَطْف بَيانِ?

- What is an عَطْف النَسْقِ ?

- What’s the meaning of :

- و?

- أمْ?

- إمَّا

- What’re the conditions for connecting using:

- بَلْ?

- لكِنْ?

- What is the same about two words that are joined together using one of these particles?

Until next time, السلام عليكم

Like this post? Simply enter your e-mail and click “Yes, include me!” for updates

I really thank god given the time of read this topic,this details very useful for my future reference and i need further chapters kindly send me the update

سلام علیکم

هل یجب ترک مسافة بین واو و کلمة التی تلیها لواو العطف فقط أو لکل واو؟

Please send your answer to my gmail: mohsen.amiri@gmail.com