السلام عليكم,

We’ve looked in detail at all the status indicators and all the words we will see these indicators in. By now, we’re more than a third of the way into our journey through this Arabic grammar, so if you’ve been following along, you’ve come a long way! For the next few sections, we’re going to look a little bit at verbs: what kind of verbs there are, what rules they follow, and what factors will change their state. Ready? Let’s do this!

Kinds of Verbs

الأفعالُ ثَلاثَةٌ: ماضٍ وَمُضارِعٌ وَأمْرٌ, نَحْوُ ضَرَبَ وَيَضْرِبُ وَاضْرِبْ

Verbs are (one of ) three: ماض (past tense), مُضارِع (present tense), and أمر (command), like ضَرَبَ (“He struck”), يَضْرِبُ (“He strikes”) and اضْرِبْ (“Strike!”)

Verbs are divided into three kinds:

- الماضِيْ (perfect/past tense) – goes back to the time before someone is speaking

- المُضارع (imperfect/present) – refers to the same time that someone is speaking in or to the future. It’s technically not right to simply say it’s a “present tense” verb, but that’s the nearest translation. Grammarians call it “imperfect” because it hasn’t finished executing yet, which also implies that ماض (past tense) is “perfect” because it’s completed.

- أمر (command) – the speaker is seeking that something be done, so this would have to relate to the future

Some example verbs, just to give an idea:

| Perfect | Imperfect | Command | |

| To hit | ضَرَبَ (He hit) |

يَضْرِبُ (He hits) |

اضْرِبْ (Hit!) |

| To help | نَصَرَ | يَنْصُرُ | انْصُرْ |

| To open | فَتَحَ | يَفْتَحُ | افْتَحْ |

| To know | عَلِمَ | يَعْلَمُ | اعْلَمْ |

| To presume | حَسِبَ | يَحْسِبُ | احْسِبْ |

| To be noble | كَرُمَ | يَكْرُمُ | اكْرُمْ |

I’ve only translated the first row, because all the other rows work the same way. We’ve mentioned this before as well in Verbs and Particles along with the Signs of the فعل .

أحكام الفِعْل (Rules for verbs)

فَالماضِيْ مَفْتُوْحُ الآخِر أبَدًا وَالأمْرُ مَجْزُوْمٌ أبَدًا, و المُضارِعُ ما كانَ فِي أوَّلِهِ إحدى الزَوائدِ الأربَعِ التِي يَجْمَعُها قَولُكَ “أنَيت” وَهُوَ مَرْفُوْعٌ أبَدًا حَتَّي يَدْخُلَ عَلَيْهِ ناصِبٌ أو جازِمٌ

The perfect tense is always ended with fathah, and the command is always in jazm. The imperfect tense is whatever has one of the four letters that are combined in the word “أنيت”, and it is always in raf’ until something that causes nasb or jazm enters it.

The rule for the ماض (perfect tense)

The ماض is fixed upon fathah, and this fathah can be apparent or implied.

As for the apparent fathah, you’ll see it in the verb whose final root letter is normal and neither the و of the plural nor a voweled pronoun that is used for the doer attaches to the end of it. The same goes for a verb whose final root letter is a و or a ي. For example:

- أكرَمَ (“He ennobled”), قدّمَ (“He advanced”) and سافَرَ (“He traveled”) – We see the fathah on the final letter

- سافَرَتْ زينبُ (“Zaynab traveled”) and حَضَرَتْ سعادُ (“Su’ad arrived”) – The تْ used for the female doer is attached to the end. Because it is silent and not voweled, we still see the fathah on the ر

- شَقِيَ and رَضِيَ – We see the fathah on the ي

- سَرُوَ and بَذُوَ – ًWe see the fathah on the و

As for the implied fathah, then there are three reasons why a fathah will not show up:

- التَعَذُّر – Impossibility of placing a vowel. You see this in whatever ends with an ا or ى (alif maqsurah), for example دَعا and سَعى. Each of these is a past tense verb that is fixed onto an implied fathah at the end. The fathah‘s appearance is blocked by the impossibility of putting a vowel on an alif.

- المُناسَبَة – Association with a vowel. This is any verb that has the و of the plural. For example, كَتَبُوا (“they wrote”) and سَعِدُوا (“they were happy”). Each of these is a past tense verb, fixed upon an implied fathah at its end. The fathah cannot appear because the space is already occupied by the dhammah that comes with the plural و. The و in each of them is the doer, fixed onto sukun, in the status of raf’.

- دفع الكراهة – Warding off the disliked presence of four consecutive voweled letters. This is in any past tense that has a voweled pronoun for the doer at the end of it, such as the ت of the doer, and the ن of the feminine plural. For example, كَتَبْتُ (“I wrote”), كَتَبْتَ (“You wrote”), كَتَبْتِ (“You[f.] wrote”), كَتَبْنا (“We wrote”) and كتَبْنَ (“They[f.] wrote”). Each of these past tense verbs sticks to an implied fathah on the ب. The fathah can’t show because the space is taken up by a sukun that pops up to prevent having four consecutive voweled letters. Whatever is after the ب (i.e the ت, نا or ن) is the doer, in the status of raf’.

While we’re at it, I should probably show you the ending pronouns for the doer in the past tense. You can find them here.

The rule for the أمر (command)

The rule for the command is to keep it fixed on whatever is used to put the imperfect in jazm. We learned from The signs of جزم that there are only two ways to put a verb in jazm: 1) using sukun and 2) dropping the final letter.

If an imperfect verb has a normal final root letter, you’d use sukun to put it in jazm. That means that the command form of the verb is also fixed on sukun. Like the fathah used for past tense verbs, the sukun is either apparent or applied.

The apparent sukun has two situations:

- Final letter is normal and with nothing attached at the end (e.g اضْرِبْ [“Hit!”] and اكْتُبْ [ً”Write!”]). The words يَضْرِبُ (“He hits”) and يَكْتُبُ (“He writes”) both use a sukun to go into jazm, so their commands will have the sukun as well.

- The ن of the feminine plural attaches to the end (e.g. اضْرِبْنَ -“Hit, you[f.] all!”) and اكْتُبْنَ – “Write, you[f.] all!”)

The implied سكون has one situation, and that is when either the heavy or light ن of emphasis attaches to the end the verb (e.g اضْرِبَنْ and اكْتُبَنْ and اضْرِبَنَّ and اكْتُبَنَّ)

If an imperfect tense verb’s final letter is a defective (i.e. it’s one of ا – و- ي), then it is given jazm by dropping the defective letter and the command is also built on dropping the defective letter. For example:

- ادْعُ (“Invite!”) – The original verbيَدْعُوْ (“he invites”) drops the و in jazm to become يَدْعُ

- اقْضِ (“Decree!”) – The original verb يَقْضِيْ (“he decrees”) drops the ي in jazm to become يَقْضِ

- اسْعَ (“Strive!”) – The original verb يَسْعَى (“he strives”) drops the ى in jazm to become يَسْعَ

If the imperfect is one of the Five Verbs that take jazm by dropping the ن, then the command is also built on dropping the ن. For example:

- اكْتُبا (“Write, both of you!”) comes from تَكْتُبانِ (“you both write”)

- اكْتُبُوْا (“Write, all of you!”) comes from تَكْتُبُوْنَ (“you all write”)

- اكْتُبِيْ (Write! [single female])” comes from تَكْتُبِيْنَ (“you[f.] write”)

All of these present tense verbs would drop their final ن in jazm, so their command forms will be built the same way, with the same ending.

Sign of the فِعل مُضارِع

Its sign is that in its beginning is an addition from one of the four letters that are combined in the word نأتي (i.e. ن – أ – ت – ي).

The أ is for the speaker, male or female (أفهَمُ).

The ن is the for the speaker that aggrandizes himself (a.k.a. “the royal we”), or for the speaker who others are with (نفهم).

The ي is for 3rd person (يَقُومُ).

The ت is for the 2nd person (“you”) or feminine 3rd person (“she”), as in:

أنتَ تَفهَمُ يا مُحمدُ واجِبَكَ (“You understand, O Muhammad your duty”), and

تَفهَمُ زَينَبُ واجِبها (“Zaynab understands her duty”)

Sometimes a verb will have one of these letters at the beginning but still not be in the present tense. That can happen if one of two things happen:

- If these letters are not an addition to the word, but rather from the actual root letters of the verb, such as أكَلَ (the أ at the beginning is actually part of the original root) and نَقَلَ (the ن is a root letter)

- They are an addition, but not because of a meaning (such as the 1st/2nd/3rd person) that we mentioned here

The rule for the مُضارِع (imperfect tense)

Whatever the nun of emphasis or the ن of the feminine plural does not attach to can change in ending.

Whatever the heavy or light nun of emphasis attaches to is built on fathah, for example لَيُسْجَنَنَّ و لَيَكُوناً مِن الصاغِرين. The last letter in the word يُسْجَنُ (“he is imprisoned”) takes a fathah before adding the heavy nun (نَّ) of emphasis, and the same thing for يَكُونُ taking a fathah on its final ن before adding a light nun (نْ).

يُسْجَنُ + نَّ = يُسْجَنَنَّ

يَكُوْنُ + نْ = يَكُوْنَنْ

If the ن of the feminine plural attaches to it, then it’s built on sukun (e.g. وَالوالِداتُ يُرْضِعْنَ أولادَهُنَّ)

يُرْضِعُ + نْ = يُرْضِعْنَ

The ع is the last letter of the present tense and takes a sukun before add the nun of the feminine plural

If a present tense verb doesn’t have one of these nun‘s of the emphasis or feminine plural attached to it, then it can change ending. By default it will be in raf’ as long as something else doesn’t come and change its state to nasb or jazm. For example, ٌيَفهَمُ مُحَمَّد (“Muhammad” understands”):

- The verb يَفْهَمُ is a present tense and is in raf’ because nothing else came to change its state. The sign of its raf’ is the visible dhammah

- The word محمد is the doer of an action, in raf’ with a visible dhammah

If something comes to put it in nasb, for example, لَنْ يَخِيْبَ مُجتَهِدٌ (“Never will one who strives fail”):

- The word لنْ is a particle used to negate something happening in the future and will put a verb into nasb

- يَخِيبَ is a present tense verb in nasb because of لَنْ, with a visible fathah

- The word مُجتَهِدٌ is the doer of an action, in raf’ with a visible dhammah

If something comes to put it in jazm, for example, لَمْ يَجْزَعْ إبراهِيمُ (“Ibrahim did not become anxious”):

- The word لمْ is particle uses to negate that something has happened (changes it to the past tense) and will put a verb into jazm

- يَجزَعْ is a present tense verb in jazm because of لَمْ, with a visible sukun

- The word إبراهيم is the doer of an action, in raf’ with a visible dhammah

From the Quran

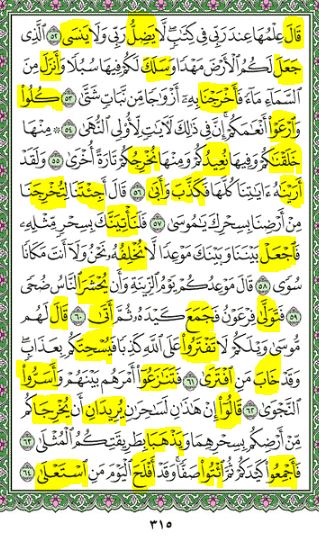

The words highlighted below from 20:52-64 are all verbs, and we’ll go through all of them. It might be a exhaustive, but this is how we learn to recognize patterns from our reading.

- Past tense verb fixed on fathah

- قالَ (“He said”), جَعَلَ (“He made it [as] …”), سَلَكَ (“He inserted”), أنْزَلَ (“He sent down”), جَمَعَ (“He gathered”), خابَ (“He failed”), أفْلَحَ (“He succeeded”)

- Past tense fixed on an implied fathah

- أخْرَجْنا (“We brought forth”), خَلَقْنا (“We created”), أرَينا (“We showed”), جِئْتَ (“You came”) – the pronoun نا (“we”) or َت (“you”) attached to the end of each is voweled (i.e. is not silent), so the letter before the pronoun will have a sukun on it, with an implied fathah.

- أبَى (“He refused”), تَوَلّى (“He turned”), أتَى (“He came”), اِفْتَرَى (“He invented a lie”), اِسْتَعْلَى (“He overcomes”) – These all end with a ى (alif maqsurah), so it’s impossible to put a fathah on them

- تَنازَعُوْا (“they debated/disputed”), أسَرَُوْا (“they kept hidden”), قَالُوْا (“they said”) – these all have the ْو of the plural attached to the end. When you use the و of the plural, you put a dhammah on the letter before it, which means the fathah that we originally wanted to put on it can only be implied

- Present tense verb with nothing attached.

- In raf’ using a dhammah

- يَضِلُّ (“He errs”), نُعِيْدُ (“We return”), نُخْرِجُ (“We bring out”), نُخْلِفُ (“We fail to keep”)

- يَنْسَى (“He forgets”) – The dhammah is implied because we can’t put any vowel on ى

- In nasb using fathah

- تُخْرِجَ (“You drive out”) – It is in nasb because of the particle لِ (“so that”)

- يُحْشَرَ (“They are gathered”) – In nasb because of the particle أنْ

- يُسْحِتَ (“He destroys/eradicates”) – In nasb because of the فَ before it that shows a causal relationship (i.e “Don’t invent a lie against Allah resulting in which He will destroy you”)

- In jazm using sukun – No examples on this page

- In raf’ using a dhammah

- Present tense verb fixed on fathah because of a ن of emphasis

- نَأتِيَنَّ is emphasized form of نأتِيْ (“we will come”). When we add a ن for emphasis, the last letter before it will stick to fathah

- Five Verbs

- In raf’ by keeping the final ن

- يُرِيْدَانِ (“they both want”)

- In nasb by dropping the final ن

- يُخْرِجا (“they both drive out”) – In nasb because of أنْ before it

- يَذْهَبَا (“they both go”) – In nasb because it is connected by وَ to another nasb-ized verb

- In jazm by dropping the final ن

- تَفْتَرُوْا (“you all invent a lie”) – In jazm because of the لا (“Don’t!”) before it

- In raf’ by keeping the final ن

- Commands – Always built the same way the present tense looks like in jazm

- Built on sukun

- اجْعَلْ – command for تَجْعَلُ (“you make/appoint”)

- Built on dropping the final ن – the command form of one of the Five Verbs

- كُلُوْا (“Eat, you all!”) from تَأكُلُوْنَ (“You all eat”)

- ارْعَوْا (“Tend, you all!”) from تَرْعَوْنَ (“You all tend”)

- أجْمِعُوا from تُجْمِعُوْنَ (“you all resolve together”) and ائْتُوْا from تَأتُوْنَ (“you all come”)

- Built on sukun

Next up, إن شاء الله: Reasons why a verb will go into nasb.

Questions

- How many division do verbs divide into?

- What is the ماض (past/perfect tense)?

- What is the مضارع (present/imperfect tense)?

- What is the أمر (command)?

- Give 1-2 examples for each kind of the verb.

- When is the verb fixed on the a visible fathah?

- For each situation that the past tense is fixed on an implied/hidden fathah, bring two examples and explain why it’s hidden

- When is the command built on a visible sukun?

- For each situation that the command is build on the apparent sukun, bring an example

- When is the command fixed upon an implied sukun? Give an example of that.

- When is it built upon dropping the defective letter?

- When is it fixed upon dropping the ن?

- With an example, what is the sign of the present tense?

- What are the meanings that the أ of the present tense comes for?

- The meaning of the ن?

- What is the rule for present tense verbs?

- When is the present tense built on fathah?

- When is it built on sukun?

- When is it in raf’?

Until next time, السلام عليكم و رحمة الله و بركاته

Like this post? Simply enter your e-mail and click “Yes, include me!” for updates

Assalam Alaikum

How do I understand the meaning of Qaala in future i.e “will say” in Quran 14.22, as the verb is in past tense form, is there any rules for it. Please clarify.

Jazak Allahu Khairan.

I want to go to Arabic language

Good