السلام عليكم و رحمة الله,

When something’s as important as Arabic, you can bet that the discussions about the reasons to learn it and why it’s so important will abound as they have through the centuries right up until our time. I’m going to give my own take. It is edgy, it is opinionated, but don’t let that stop you from going through it. Keep in mind that when I say “Arabic”, I mean the pure Arabic that was present during final era of revelation, not what is known as “dialects” today.

Arabic is the language of Islam

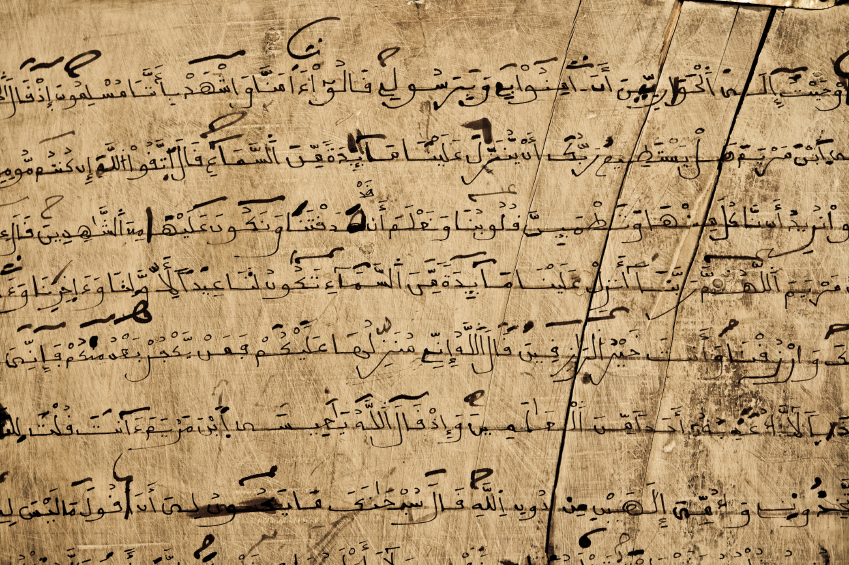

This is something we really need to wrap our heads around to understand how important Arabic is. All the primary sources are in Arabic. All our rituals use them. The understanding of many Islamic concepts go back to what the words originally mean in Arabic. It is a symbol of Islam, so much, that for much of history, the Muslims were simply called “the Arabs”, because the world closely related Arabic and Islam together (i.e. that the Muslims are an Arabic-speaking nation).

Is it amazing that for centuries there were kings in Europe with fair skin and light-colored eyes who spoke Arabic? That is because these dynasties, while far in time and place from the birth of Islam, knew that Arabic was and will always be the “official language” of Islam. They used it for both religious duties and for governance. How far we’ve come from that standard!

In fact, it is because of Islam that pure Arabic has been preserved at such a high level. There is no Islam without Arabic, and there is no Arabic without Islam.

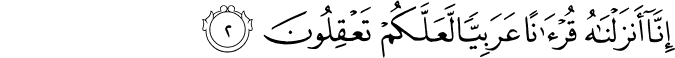

My point is not that it is wrong to learn about Islam in other languages, if you’re a beginner, but you will never have more than a beginner-level knowledge without Arabic. If you want to progress further, you will have to consult the works of the scholars, and that means learning the language of the scholars. The whole point of the Quran being in Arabic is so that you can grasp it. Just look:

Every one of us has to learn from the Quran and Sunnah to the level where we can perform our duties to our Lord and to each other properly, so whatever Arabic we need in order to learn that is also mandatory.

Arabic is the language of the love of your life

If someone captures your heart, you want to find out as much as you can about them. You find out where they live, who their friends are, what classes they’re taking, which way they take home, basically everything about this beautiful, fascinating person…. [Read more…] about Why should you learn Arabic?

السلام عليكم ورحمة الله وبركاته,

السلام عليكم ورحمة الله وبركاته,